When the summer transfer window closed on 31st August across most European football leagues last week, the amount of money spent had reached another record: clubs in the top 5 leagues in Europe had completed almost 1,700 deals worth close to £4bn/€4.4bn. When so much money changes hands, question crop up about its origins. Alex Duff and Tariq Panja, the authors of “Football’s Secret Trade”, reveal in their book how investors and speculators have infiltrated the football transfer system. Planet Compliance spoke to Alex about how money is moved around, the helplessness of football’s governing bodies and whether financial regulators should have an interest.

A billion dollar business

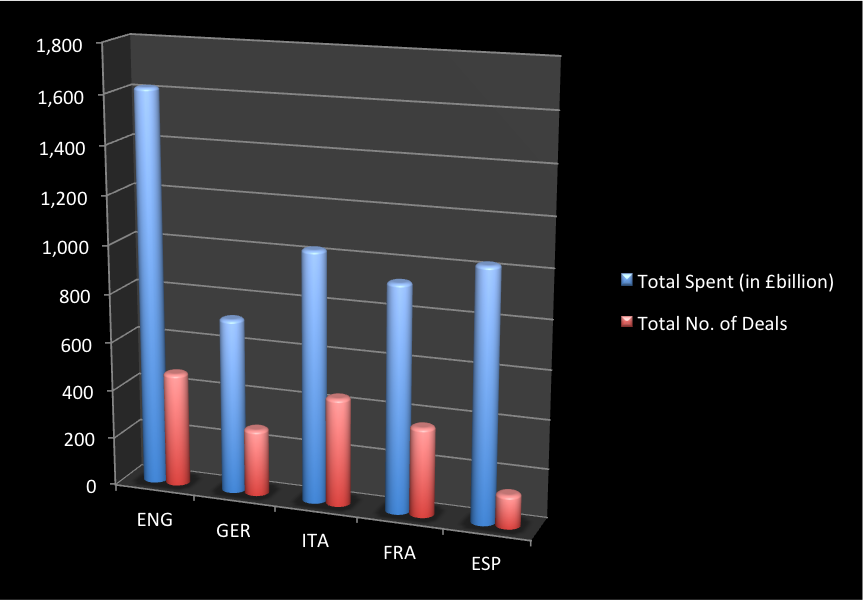

Every year football teams in Europe can buy new players only in two designated transfer windows, periods of 4-8 weeks that culminate in the deadline day when clubs try to rush through last minute deals and fans around the globe are fixed to news outlets and social media channels. It’s almost as if it counted more who their favourite teams signed than the actual performance during the season. Because of the increasing TV rights fees (the English Premier League, for instance, has sold its television rights for the period from 2016 to 2019 for a whopping £5.136bn) and the money brought in by wealthy owners like Russian oligarchs or Arabian sheikhs, the transfer fees have exploded over time as well. For example, Paris Saint-Germain, a club basically owned by the state of Qatar through its Oryx Qatar Sports Investments structure, spent the record fee of £200 for the Brazilian footballer, Neymar this year. With the summer transfer window between July and August more important than the mid-season winter transfer window in January, the English clubs have broken the spending record for the sixth consecutive year by investing more than £1.4bn. The other top European leagues are not far behind though with both Italian and Spanish clubs spending £1.03bn, French teams £931m and German clubs £720m.

| Total Spent (in £billion) | Total No. of Deals | |

| ENG | 1.620 | 469 |

| GER | 720 | 274 |

| ITA | 1.030 | 444 |

| FRA | 931 | 365 |

| ESP | 1.030 | 135 |

Source: The Guardian

Who’s in charge?

The transfer system is loosely controlled by football’s governing bodies, i.e. the global Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) and regional governing bodies like the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA). Duff and Panja describe in their book how badly equipped these bodies are though to effectively govern the process, in particular when they tell the story of one FIFA official who unsuccessfully tried to clean up the system but later left frustrated by the obstacles he encountered inside the organisation.

One door closes, another open.

At the centre of the book, however, are the practices of a number of investors though that uses football clubs and players to secretly make hundreds of millions of profits. One way to do so is to cater to the club’s ever increasing need for new funds. Especially following the Global Financial Crisis of 2007/08, traditional financing like loans from banks were hard to come by for football clubs and opportunists stepped in to fill the void and provide clubs with loans. With little or no regulation governing the sector, another way that is described in much detail in the book for investors to take advantage of the transfer market is to setup a company structures to hide the trail of the money. Often, as Duff pointed out, these involve the foundation of UK companies with nominee directors as a front to mask the true identity of the people pulling the strings.

A toothless tiger?

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an independent inter-governmental body that tackles money laundering and terrorist financing, highlighted this practices as means of laundering the proceeds of illegal activities through the football sector. The organization’s report from 2009 showed that criminals used different techniques, including the use of cash, cross border transfers, tax havens, front companies, non-financial professionals and Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs) for money laundering. Other cases show that the football sector is also used as a vehicle for perpetrating various other criminal activities such as trafficking in human beings, corruption, drugs trafficking (doping) and tax offences, FATF emphasized.

However, Duff and Panja demonstrate in their book, that despite the recommendations FATF had made in its report, very little had changed as the practice of selling players to clubs these investors use a front to immediately move them on to another to make a profit and, at best, evade taxes.

The difficulty for football’s governing bodies is that the transfer system in itself is so attractive for this kind of behavior. It is because of the large sums that have been steadily increasing over the last 30 years that so many people are chasing a share of it”, as Duff said. Only if, for instance, the money that is paid for players would be reduced, this could be limited, which is, however, an unlikely outcome, as he admitted, with the many competing interests in the sport.

Furthermore, given FIFA’s own recent corruption scandals, the organisation is not in the best position itself to force through stricter rules. Another aspect Duff pointed out in this context is that in particular the national governing bodies are often too close to the clubs they oversee and lead to too little regulation of financing practices. At the same time, getting involved in sports seldom is popular for politicians and governments, which in turn creates a grey area similar to other areas of shadow banking.

Financial Regulators to the rescue?

So, what could be a solution. Should financial regulators step in considering the amount of money that is at stake? Duff agreed that it could be a possibility and pointed to the French and UK government, for example, that opened investigations in the use of image rights agreements between players and clubs that are often used to circumvent tax obligations. He criticised though that most of the investigations were ad-hoc measures without a systematic approach towards corruption and other wrongdoing in the football sector.

The most proactive tax authority? Argentina!

A surprising exception of regulatory activity can be found in Argentina, Duff explained. The tax agency in Argentina established jurisdiction to look into player deals with a lot of players moving overseas but little tax revenue flowing back into the country and tries to crack down on the evasive behaviour.

Light at the end of the tunnel?

On the whole Duff was sceptical though as to any improvement in the short term. As a result of discovering the influence of investors in the transfer system, FIFA had introduced a ban of such practices but investors could often find a way around and with the limited resources of the governing bodies prevention of, for instance, money laundering was close to impossible for them. As Duff said, a lot of the deals he found in the last twenty years were going through the UK for tax reasons and “with thousands of new company foundations each week, they couldn’t possibly keep up with”. (According to the UK’s Companies House between April and June 2017, there were 152,411 company incorporations and 114,756 dissolutions in the UK)

“Football’s Secret Trade: How the Player Transfer Market was Infiltrated” by Alex Duff and Tariq Panja is published by Wiley and Bloomberg Press. For more information on the book and its authors, have a look here.