Some considered 3 January 2018 to be the end of banking as we know it, doomsday, Armageddon. For several years the tension and anticipation had been building up and the final weeks of 2017 were extremely ones in many compliance departments in order to prepare for the arrival for MiFID II. And the party is far from over. As the German regulator recently pointed out, MiFID II compliance from the start was difficult to achieve and some financial institutions are making only slow progress in catching up. However, as the influx of guidelines, final reports, updated Q&As and other updates that have seen been published by the European authorities shows it was never intended to end in January. With the month of May drawing to an end, we can assert that regardless of the various bank holidays, it was an extremely busy month for MiFID updates.

One of the areas that already was a cornerstones of the original MiFID, is Best Execution and its revision has raised the bar further. In another instalment of our series of nutshell articles that summarise and explain the essentials of MiFID II. This time, we look at the changes that were brought in by the new MiFID II Best Execution rules and describe how it works in practice.

The birth of MiFID II

To put these changes in context, it is useful though to properly understand at the legislative process upon which these rules were built. This process wasn’t always as complex as it is now. Well, yes it was always complex but in a different way. For many years the financial industry in particular had been complaining about the fact that lawmaking in the EU was drawn-out and not very efficient. With a growing number of member states, this wasn’t going to get any better, so around the turn of the millennium it was decided that a group of experts would look into ways how to improve this process. The committee developed the Lamfalussy Process, which was named after the chair of the EU advisory committee that created it, Alexandre Lamfalussy. It is a model for the (in theory faster and better) creation of financial service industry regulations and aims to provide several benefits over traditional lawmaking: more-consistent interpretation, convergence in national supervisory practices, and a general boost in the quality of legislation on financial services.

MiFID II/MiFIR is one of the key regulatory initiatives in the Financial Services Industry right now. It is a massive challenge for banks and firms to adapt to the changes in the legislative framework and even the authorities are struggling with the workload – see the recent postponement by one year until 2018 since ESMA couldn’t get their homework done in time.

There seem to be dozens of legislative documents flying around that appear to be relevant, starting with the original Directive and Regulation to delegated regulations, technical advice, regulatory and technical standards or guidelines on some particular aspect. Perhaps it is not a bad idea to take a step back and look at the mechanics of the underlying process of legislative initiatives in the EU on the example of MiFID II/MiFIR.

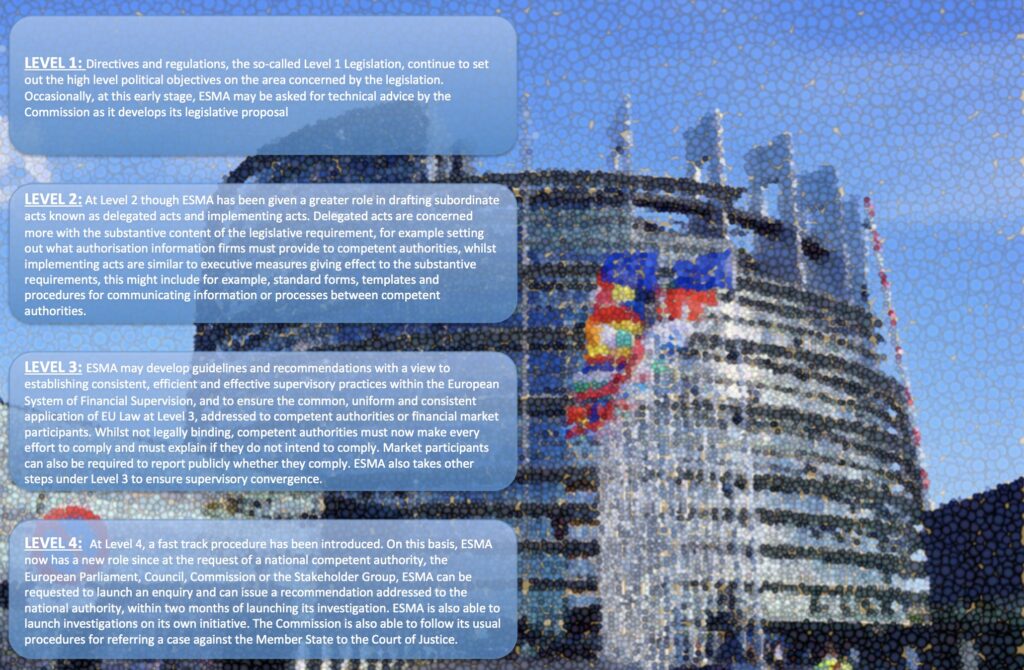

When talking about legislative power in the context of regulations and documents issued by ESMA, it is often referred to the so called Lamfalussy Process. This is an approach to the development of financial service industry regulations used by the European Union, which was originally developed in March 2001 and named after the chair of the EU advisory committee that created it, Alexandre Lamfalussy. It is composed of four “levels,” each focusing on a specific stage of the implementation of legislation. In principle, the Lamfalussy Process.

The original document of European Commission that outlines the application of the Lamfalussy Process can be found here, but since introduction of the EU supervisory authorities, (and in particular ESMA) the process has been amended to award these specialist authorities greater involvement and powers. The ESMA regulation (see full text here) has introduced the following updated four level framework:

These are the basics and though this has worked rather well for other legislative initiatives, MiFID II/MiFIR have been a whole different story. It’s ambition was this that the lawmaking process was already awarded a period to produce draft technical and regulatory standards and advice that was significantly longer than usual. Nonetheless, because of the complexity of the topic ESMA had to ask for more time, which resulted in the extension of the MiFID deadline from its original application in 2017 to 2018 to give regulators and market participant more time to prepare for the exceptional technical implementation.

Why then do we still see new acts of regulation with regard to MiFID II? For starters, because the EU’s MIFID II/MiFIR regulation has raised the bar a fair bit in terms of pre- and post-trade transparency, an ongoing valuation process is required to allow adaption in light of the impact of the new norms to avoid unintended results. Or as ESMA points out in its Q&A updates, “to promote common supervisory approaches and practices in the application of MiFID II/ MiFIR”. So, one of the areas that continues to concern financial institutions and their compliance departments (and other functions) is Best Execution and that is likely to continue to be the case with a number of reporting deadlines looming for the first time over the coming months.

What was BestEx under MiFID I?

When the original Markets in Financial Instruments Directive was introduced in 2007 it was because the European lawmakers had decided it was time to harmonise European financial markets to offer investors a high level of protection and to allow investment firms to provide services throughout the Community, being a Single Market, on the basis of home country supervision.

In order to achieve the objective of improved investor protection, MiFID introduced in its article 21 the obligation to execute orders on terms most favourable to the client and to take all reasonable steps to obtain the best possible result for their clients when executing orders. To measure the outcome, the best possible result should be determined by a number of execution factors: price, costs, speed, likelihood of execution and settlement, size, nature or any other consideration relevant to the execution of an order.

If you were one of the people working in Compliance departments across the industry, you will remember that this concept was one of the biggest challenges for financial institutions both in terms of implementation and evidence.

MiFID also introduced the term MTF, short for Multilateral Trading Facility. An MTF is basically a self-regulated financial trading venue. They were introduced to increase competition and create alternatives to the traditional exchanges. Naturally, the increased number of trading and execution venues added to the complexity of the task.

However, from early on it became apparent that the Best Execution requirements weren’t far reaching enough. The emergence of a new generation of organised trading systems alongside regulated markets or the rise of rise of algorithmic trading made it necessary to tweak the existing framework to ensure the efficient and orderly functioning of financial markets and avoid that these new players benefit from regulatory loopholes.

What is new under MiFID II & MiFIR?

As a result, MiFID II and MiFIR together with a multitude of 2nd, 3rdand 4thlevel acts have introduced a number of new rules with regard to Best Execution.

They can roughly be categorised into three groups: 1) the obligation to obtain best execution, 2) the requirements regarding the transparency of execution and to publish data on execution quality; and 3) the revision of the best execution policy.

From all reasonable to all sufficient steps

The first MiFID obliged firms to take all reasonable steps to obtain the best possible result for their clients when executing orders. If there had been any doubt that MiFID II would raise the bar with regarding what would be required to stay compliant, ESMA made it clear in its Q&As on Best Execution in 2016. ESMA said that “MiFID II now instead requires firms to “take all sufficient steps to obtain, when executing orders, the best possible result for their clients taking into account price, costs, speed, likelihood of execution and settlement, size, nature or any other consideration relevant to the execution of the order”. […] When designing their execution policies and establishing their execution arrangements, firms will have to ensure that the intended outcomes can be successfully achieved on an on-going basis. This is likely to involve the strengthening of front-office accountability and systems and controls according to which firms will ensure that their detection capabilities are able to identify any potential deficiencies. This will require firms to monitor not only the execution quality obtained but also the quality and appropriateness of their execution arrangements and policies on an ex-ante and ex-post basis to identify circumstances under which changes may be appropriate. An example of ex-ante monitoring would be to ensure that the design and review process of policies is appropriate and takes into account new services or products offered by the firms. Accordingly, an ex-post monitoring may be to check whether the firm has correctly applied its execution policy and if client instructions and preferences are effectively passed along the entire execution chain when using smart orders routers or any other means of execution.”

The Q&As also proposed that firms should employ a combination of front office and compliance monitoring as well as using systems that rely on random sampling or exception reporting. Furthermore, ESMA made it clear that there are reporting models need to be in place to make sure that the results of ongoing execution monitoring are escalated to senior management and/or relevant committees, and fed back into execution policies and arrangements to drive improvements in the firm’s processes.

ESMA provided some relief though as the new rules weren’t supposed to be interpreted to mean that a firm must obtain the best possible results for its clients on every single occasion. “Rather, firms will need to verify on an on-going basis that their execution arrangements work well throughout the different stages of the order execution process. ESMA expects firms to take all appropriate remedial actions if any deficiencies are detected so that they can properly demonstrate that they have taken “all sufficient steps” to achieve the best possible results for their clients.”

Best execution criteria

The Best Execution criteria mentioned above from Article 27 of MiFID II – price, costs, speed, likelihood of execution and settlement, size, nature or any other consideration relevant to the execution of the order – must be evaluated against the background of the client and the circumstances of an order. For instance, in the case of an execution for a retail client, the best possible result shall be determined in terms of the total consideration, representing the price of the financial instrument and the costs relating to execution, which shall include all expenses incurred by the client which are directly relating to the execution of the order, including execution venue fees, clearing and settlement fees and any other fees paid to third parties involved in the execution of the order.

Moreover, in accordance with Article 64 of the MiFID II Delegated Regulation investment firms need to take into account the following when they determine the relative importance of the factors from Article 27 of MiFID II

(a) the characteristics of the client including the categorisation of the client as retail or professional;

(b) the characteristics of the client order, including where the order involves a securities financing transaction (SFT);

(c) the characteristics of financial instruments that are the subject of that order;

(d) the characteristics of the execution venues to which that order can be directed.

With the extension to other asset classes, the assessment of execution criteria has to be seen in a different light however. What is true for equity instruments, does not necessarily apply to fixed income products or derivatives that are executed over the counter (OTC), where there is often less liquidity or clarity on price and volume. Nonetheless, the new rules make it clear that firms still need gather market data used in the estimation of the price of such product and, where possible, by comparing with similar or comparable products, in order to check the fairness of the price proposed to the client when executing orders or taking decision to deal in OTC products. A suitable approach therefore is the competing quotes from a limited number of counterparties that contains an element of reasonability while still being sufficient according to the new Best Execution framework.

Needless to say that since MiFID II extends as well the scope of financial instruments to include commodity derivatives and emission rights the best execution obligation applies for these, too.

Naturally, and regardless of the above, if the client provides a specific instruction the investment firm must execute the order following these instructions. A firm will then be compliant with its Best Execution obligation regardless whether the above criteria like best price, lowest costs or speed of execution etc.

are met or not.

Execution venues

The introduction of MTFs under MiFID was only the beginning of a broader competition amongst execution venues. In addition to regulated markets and MTFs, MiFID II extends this list to organised trading facilities (OTFs), systematic internalisers (SIs), market makers, other liquidity providers, and comparable third country entities. ESMA has defined other liquidity providers to include firms that hold themselves out as being willing to deal on own account, and which provide liquidity as part of their normal business activity, whether or not they have formal agreements in place or commit to providing liquidity on a continuous basis”. This is in order to give flexibility for ESMA and national competent authorities to determine when a firm is considered to provide liquidity as part of their normal business activity.

In a situation where more than one competing venue to execute an order for a financial instrument is available, in order to assess and compare the results for the client that would be achieved by executing the order on each of the execution venues listed in the investment firm’s order execution policy that is capable of executing that order, the investment firm’s own commissions and the costs for executing the order on each of the eligible execution venues need be taken into account in the decision where to execute the order eventually.

Also, where investment firms apply different fees depending on the execution venue, the firm shall explain these differences in sufficient detail in order to allow the client to understand the advantages and the disadvantages of the choice of a single execution venue. If the firm asks its clients to choose an execution venue, the information provided to the client must be fair, clear and not misleading information to ensure that the client from chooses a execution venue rather than another not only on the sole basis of the price policy applied by the firm.

Execution Transparency and Disclosure

The transparency of execution and an increased level of disclosures is a key element to provide more clarity on the functioning of financial markets and better protect investors. MiFID II therefore introduced the obligation for firms and execution venues to produce a number of periodic reports to demonstrate the quality of and compliance with its best execution obligations.

Annual assessment report of execution quality of execution venues

In accordance with the obligations set out in RTS 27, execution venues are required to produce quarterly reports with regard to the quality of their execution including the publication of data on price, costs and likelihood of execution. In turn, investment firms are also required to publish an assessment of execution quality obtained on all execution venues used by the firm. In particular, investment firms must publish for each class of financial instruments a summary of the analysis and conclusions they draw from the detailed monitoring of the quality of execution obtained on the execution venues. This information will allow investors to assess the quality of execution and will help them to assess the effectiveness of the monitoring of execution policies carried out by investment firms.

Annual report on the top five execution venues and quality of execution obtained

MiFID II requires investment firms who execute client orders to summarise and make public on an annual basis, for each class of financial instruments the top five execution venues in terms of trading volumes where they executed client orders in the preceding year and information on the quality of execution obtained. Firms also need analyse their detailed monitoring of the quality of execution obtained on the execution venues and publish a summary of this analysis for each class of financial instruments. Firms also have to make a distinction based on whether they execute the order directly or if they transmit the order for execution to another investment firm, which could result in two separate reports. If a firm provides both the services of order execution and transmission of orders to other firms, they will need to provide two separate reports in relation to these services. The details of the content that needs to be provided and the format was explained in RTS 28. ESMA has stated that financial institutions should keep each report available in the public domain in a machine-readable electronic format for at least two years.

Quarterly execution report

As mentioned above, execution venues are required to produce quarterly reports with regard to the quality of their execution. For an investment firm this means that if it is classified as a systematic internaliser, market maker, or other liquidity providers or operates a regulated market, an MTF or an organised trading facilities, it is equally on the hook. The information that needs to be reported by execution venues with regard to quality of execution of transactions based on the data on price, costs and likelihood of execution can be found here.Each report must be available for a minimum period of two years in the public domain, for instance on a firm’s website in an easily identifiable location on a page without any access limitations.

Execution Policy

While MiFID I entailed the requirement for firms to establish and implement an order execution policy, MiFID II takes this obligation to another level for retail and professional clients.

To start with, an order execution policy needs to be tailored to the different asset classes. It should include, in respect of each class of financial instruments, information on the different venues where the investment firm executes its client orders and the factors affecting the choice of execution venue. It shall at least include those venues that enable the investment firm to obtain on a consistent basis the best possible result for the execution of client orders. Firms need to provide appropriate information to their clients on their order execution policy, which needs to be explained explain clearly, in sufficient detail and in a way that can be easily understood by clients, how orders will be executed by the investment firm for the client. Investment firms also need obtain the prior consent of their clients to the order execution policy.

With regard to the use of payments for order flow, the rules make it clear that a firm must not receive any remuneration, discount or non-monetary benefit for routing orders to a particular venue, which would infringe the rules on inducements or conflicts.

Where there is the possibility that client orders may be executed outside a trading venue, firms need to inform its clients accordingly and get the prior express consent of their clients before proceeding to execute their orders outside a trading venue, which can be either in the form of a general agreement or in respect of individual transactions.

In accordance with Article 66 of the MiFID II Delegated Regulation, the order execution policy needs to be reviewed at least annually together with a firm’s order execution arrangements. However, investment firms are also required to monitor the effectiveness of their order execution arrangements and execution policy in order to identify and, where appropriate, correct any deficiencies. Needless to say that this increases considerably both the work of the compliance department as well as the risk to miss something of significance or misrepresent the actual execution practices.

Efficient Best Execution monitoring is therefore becoming more and more important, especially considering that if a client requests information about policies or arrangements or how they are reviewed, firms now must answer clearly and within a reasonable time.

ESMA also clarified that it expects firms to be aware of the evolving competitive landscape in the market for execution venues operators and therefore to take into consideration the emergence of new players, new venues functionalities or execution services to determine whether or not any of these factors would support to include only one execution venue in their execution policy. Thus, firms need to regularly assess the market landscape to determine whether or not there are alternative venues that they could use.