Planet Compliance has extensively written about equity crowdfunding regulations in the past. But in case the concept of “equity crowdfunding”is new to the reader, this is not quite the same as “rewards crowdfunding”, which was popularized by the likes of Kickstarter and Indiegogo.

Rewards campaigns see backers pre-ordering something, whereas equity crowdfunding results in the money going towards an ownership stake. So, rather receiving a product once the project has funded, with equity crowdfunding, those contributing the cash become shareholders in the business doing the campaign.

The advent of equity crowdfunding has made it possible to raise seed and growth funding from non-accredited investors (the general public), without needing to go to the considerable cost of preparing a full prospectus. It has helped to fill the so-called “funding gap”, for companies needing to raise between ~US$50,000 to around US$2 million, depending on the country in which it takes place.

Being an offer of securities, equity crowdfunding has been implemented differently in each individual country. The Securities & Exchange Commission in America has one set of rules, the Financial Conduct Authority in the UK has another set, and so on.

As we will see, the more protectionist regulators have significantly stifled the development of equity crowdfunding, while the more liberal regimes have ended up being more effective, through self-policing driven by competitive pressures originating from the equity crowdfunding platforms.

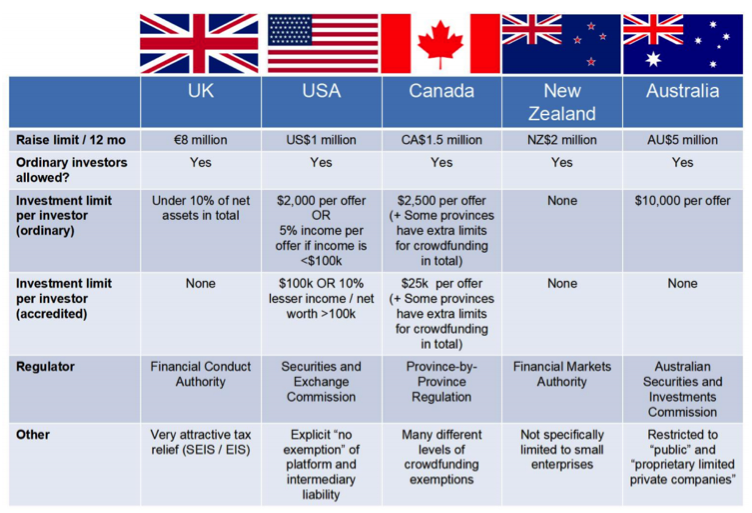

Regulatory Comparison

While it is difficult to cleanly summarize complex securities regulationsacross multiple jurisdictions, the below table attempts to do so.

Commentary

The United Kingdom regulators have taken a rather liberal approach to equity crowdfunding oversight. They have the highest maximum raise limit out of any of the five. But despite the light-touch regulations, the leading platforms like Seedrs, Crowdcube and Syndicate Room still do a thorough evaluation of the companies that arrive on their doorstep. These platforms believe that it is their own best interest to be selective over which companies they will choose to work with, so as to grow the trust of their investors. So, the UK’s success in becoming the world leader in equity crowdfunding is grounded in commercial considerations. The UK has also been boosted through the highly attractive tax incentives on offer, through the Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme (SEIS) and Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS) for startup investing. These tax breaks allow investors to offset the money they invest against their existing tax liability.

The US regulations came into force in 2016, under Title III of the JOBS Act. US-based companies can raise up to US$1.07 million (an amount which rises annually, along with inflation), in any 12 month period. This relatively low maximum restricts the use of equity crowdfunding to very early-stage companies. In addition to Title III crowdfunding, there are Reg A+ and Reg D offerings, both of which resemble more “light IPO”capital-raisings, rather than the reduced-disclosure offer documents that equity crowdfunding is best known for. The American reputation for requiring very fulsome regulatory filings has reared its head in Title III equity crowdfunding, insisting on much more prescribed capital-raising documents than the UK.

Canada’s regulations are even more restrictive. Every Canadian province has their own securities regulator, rather than a single regulator at the nationwide level. 13 sets of rules rather than one set has significantly stunted Canada’s equity crowdfunding ecosystem. For example, it is difficult (if not impossible) for a platform in British Columbia to accept a company registered in Ontario. The Canadian “Crowdfunding Exemption”which came into effect in January 2016 has been disappointing, as it still imposes too much cost and disclosure burden to be a realistic option for the startups that it was supposed to help. Although these rules were well-meaning (to protect investors), but the real effect has been to make equity crowdfunding impossible in practice, even though it is possible in law.

Relative to New Zealand’s small size, equity crowdfunding has enjoyed significant interest there. Angel and venture capital funds are participating in equity crowdfunding as cornerstone investors. Uniquely, there is no cap on what ordinary investors are allowed to invest. The securities regulator has also elected to take a relaxed approach to disclosure – in stark contrast to the highly prescriptive US and Canadian rules. There were concerns that this laissez-fair attitude would result in a “wild west”of uncontrolled capital raising, but this has proven not to be the case. Like in the UK, the platforms are self-policing the industry. While many platforms opened for business when the rules first came through in 2014, most have now closed up – leaving just a few, stronger ones to carry on.

Australia was the last of the five to make equity crowdfunding for ordinary investors legal. The biggest complaint about the Australian rules is that only “public”and “proprietary limited”companies are allowed to use them. This is in contrast to the more-straightforward and less admin-heavy private company structure that startups and early-stage ventures tend to favor. If they aren’t already “public”or “proprietary limited”, it means that companies must transfer to a less-than-desirable company structure if they want to use equity crowdfunding in Australia.

Lessons

The results from these different approaches shows that the rules must be supportive for this new form of company financing to really take root. While protecting investors is unquestionably important, when the cost-to-comply grows too high, it ends up becoming too difficult for cash-constrained startups to consider. This has been especially the case in Canada, where – although equity crowdfunding is legal – almost no activity is taking place.

By contrast, New Zealand and the United Kingdom show the outcome of a more open regulatory approach. Even in the absence of restrictive regulation, industry best-practice evolves to protect investors, because the platforms all want to develop a reputation for working with the best companies. By letting innovation grow without over-regulating it, New Zealand and the United Kingdom show that equity crowdfunding can become an important and welcome addition to the early-stage financing landscape.

Nathan Rose is the bestselling author of Equity Crowdfunding. He has appeared at crowdfunding events all over the world. Today, he runs the website www.startupfundingsecrets.io, to help startups & growing companies to gain marketing exposure and raise investment money at the same time.